On “the pleasures of the table”, according to Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin and M.F.K Fisher.

EPICUREAN MASTERPIECE

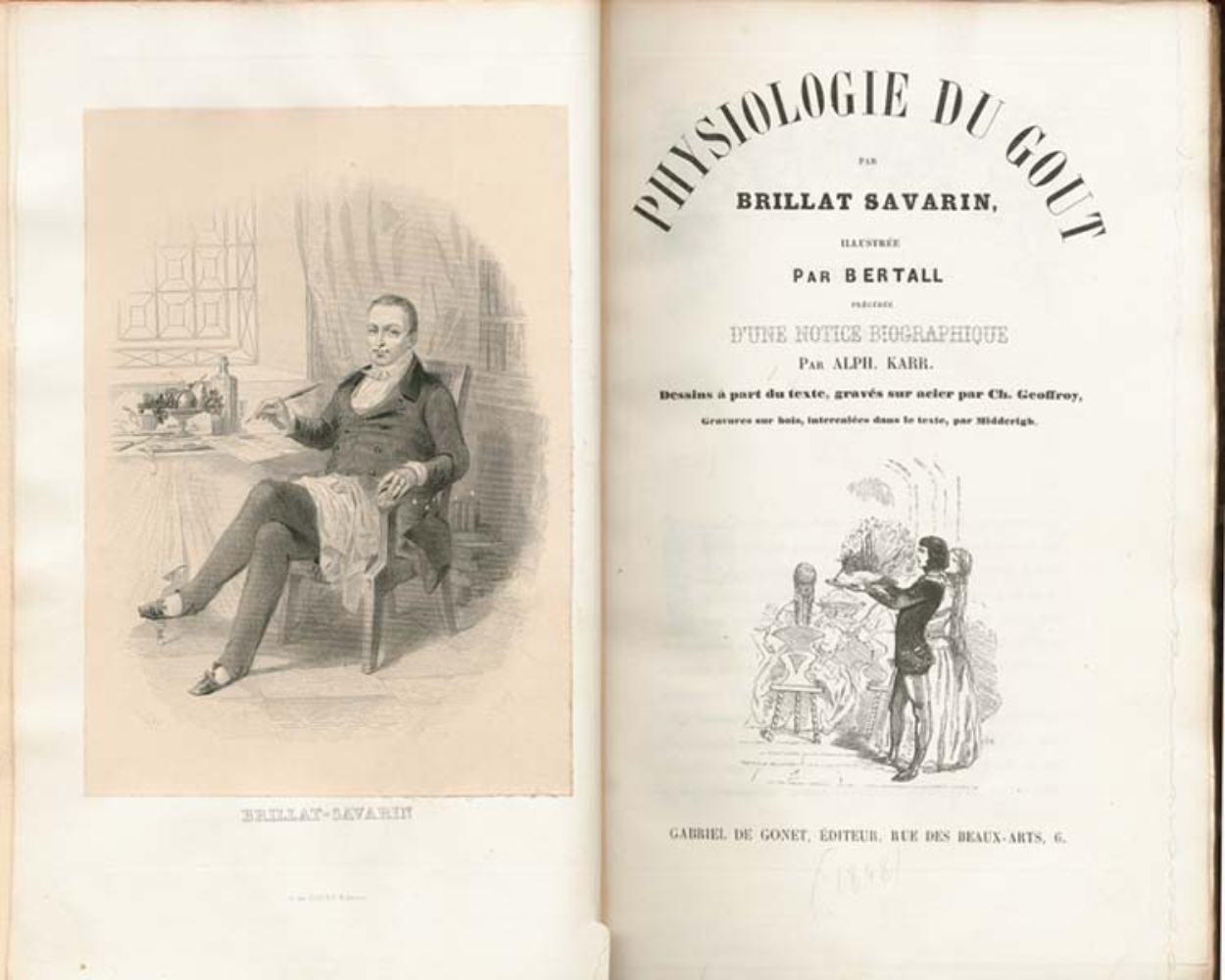

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) was a respected lawyer, politician, gourmet (not ‘gourmand’; read why here) and author of one of the most influential books in food history: Physiologie du goût (1825). The book, which took him three decades to write, is an epicurean masterpiece full of history, philosophical reflections, witty anecdotes and recipes that cover just about everything in the vast world of gastronomy, and beyond.

I had read bits and pieces of the book for culinary research, but had yet to work my way through the whole volume. To be honest, I was a little overwhelmed. The parts I read were a challenge in French, and it isn’t really ‘light’ reading to begin with. In fact, don’t bother picking this book up if you think you can just whizz through it. Whether the original French text, or the brilliant English translation by M.F.K. Fisher (The Physiology of Taste, 1949), which I have just finished reading. Finally. And I am so glad I have crossed it off my list.

In these past two weeks I have been hugely inspired, nodded in agreement, laughed, and at times, almost wanted to cry. Interestingly, when Brillat-Savarin submitted his manuscript, it was rejected. But he was determined and printed five hundred copies himself, just months before his death on January 21st 1826. That his book was a product of passion and became such an immense success moves me. Especially in this time of cookbook mediocrity when all it takes to get a book deal is a large following on social media.

ON THE PLEASURES OF THE TABLE

There are so many parts of the book which I am eager to share with you, and I will cover bits and pieces in a few posts, but I encourage you to read it yourself. One part which especially resonated with me (and which translator M.F.K. Fisher based one of her essays on) was The Influence of Gourmandism on Wedded Happiness. I have been very happily married for twenty-one years, and yes, what Brillat-Savarin writes is true. At least for us:

“A married couple who enjoys the pleasures of the table have, at least once a day, a pleasant opportunity to be together; for even those who do not sleep in the same bed (and there are many such) at least eat at the same table; they have a subject of conversation which is ever new; they can talk not only of what they are eating, but also of what they have eaten, what they will eat, and what they have noticed at other tables; they can discuss fashionable dishes, new recipes, and so on and so on; and of course it is well known that intimate table talk is full of its own charm (…). On the other hand, a shared necessity summons a conjugal pair to the table, and the same thing keeps them there; they feel as a matter of course countless little wishes to please each other, and the way in which meals are enjoyed is very important to the happiness of life.”

After our daughter was born (nearly nineteen years ago), we made a point of having a date night at home every Saturday. We cook together, play records, open a nice bottle of wine, light candles and have the most interesting (or funniest) conversations. We look forward to these special evenings, and they are not only the highlight of our week, they are priority. Because we are a priority. For us, cooking and sharing “the pleasures of the table” as Brillat-Savarin would say, is one of the many reasons why we have such a strong marriage. It doesn’t end with the Saturday dinner either. We also have a Saturday lunch date, and during the week, we regularly clink glasses, light the fireplace and the candles, and simply enjoy each other’s company.

In her essay Love in a Dish, M.F. K. Fisher gives the story of a couple who does not share a love for food, and even while sitting across from each other at a restaurant, are worlds apart. He’s wolfing down his steak (“good meat, that’s all a man needs”) and she’s nearly bored to tears, with a blank stare on her face. She advises:

“Perhaps the two of them should read or re-read Brillat-Savarin’s book. In it he would make clear to them that a healthy interest in the pleasures of the table, the gastronomical art, can bring much happiness.”

I leave you with the following observation, also from her essay:

“There can be no warm, rich home-life anywhere else if it does not exist at the table, and in the same way there can be no enduring family happiness, no real marriage, if a man and a woman cannot open themselves generously and without suspicion one to the other over a shared bowl of soup as well as shared caress (…). Then and only then, they will find that they can face each other warmly and gaily across the table again, and that even that steak-and-potatoes, when they have been prepared with a shared interest and humor and intelligence, can be one of the great pleasures which leads to another, and perhaps — who knows — an even greater one.”