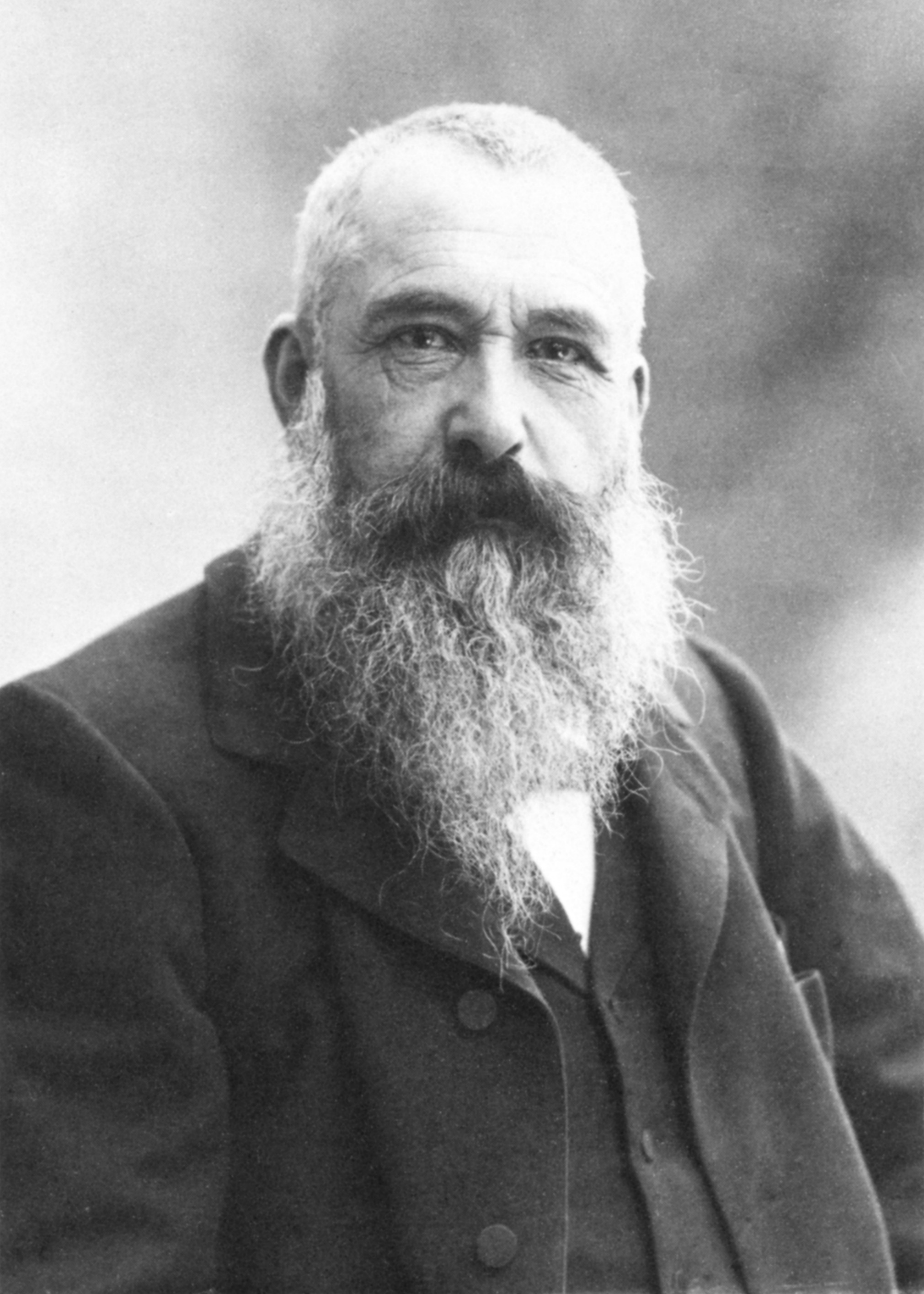

Claude Monet was not only the father of Impressionism, but he was also a true gourmet.

HIS LIFE AND LOVE FOR GOOD FOOD

Monet was born in Paris on November 14th 1840. At the age of five, he moved to Le Havre, Normandy with his family. His love of art saw him returning to the French capital where he studied and met contemporary painters such as Renoir, Sisley, Bazille, Morisot, Degas and Pissarro. In 1874, he exhibited his works under the Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs et Graveurs. At their first exhibition, Monet presented his Impression, Sunrise. It was painted in 1872 and shows the port at Le Havre. This very painting gave rise to the term ‘Impressionism’ (mockingly coined by journalist Louis Leroy). We can therefore say that it was in the hands of Monet, and in Normandy, that the art movement was born.

Impression, Sunrise (1872), Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

The first half of Monet’s artistic career was not one of wealth and prosperity. He hardly had enough to make ends meet, and not many applauded his artistic efforts. In fact, at a certain point, he was so overwhelmed by his troubles that he even attempted suicide by jumping into the Seine. In 1879, his wife Camille also died, leaving him with two young sons.

Things really started to look better in 1883 when he began to sell more paintings and moved to Giverny. There, he first rented a home close to the Seine, which by 1890, he was sufficiently wealthy enough to buy. It would become his place of artistic and personal refuge, and one that would inspire him for more than forty years. Monet lovingly decorated his house, choosing the vivid hues that would brighten each of the rooms, hanging Japanese prints on the walls throughout, and carefully designing several exquisite gardens, including the one with water lily ponds in 1893 that would feature prominently in his works.

From the airy, blue and white kitchen (which was above the ground, something quite unusual at the time), his cooks could look outside and admire the lush flower gardens that graced the terrace as they prepared beautiful meals. When the weather was fair, it was there that Monet would welcome guests for lavish lunches made with the freshest ingredients. His yellow dining room, of course, with its table that was large enough to seat fifteen, was also the scene for many a sumptuous feast. You would think that the conversations that ensued at Monet’s table revolved primarily around art, but in fact, food was the topic of choice.

Monet’s team of gardeners grew a wide variety of aromatic Mediterranean herbs and vegetables, including rosemary, mint, courgettes, tomatoes and asparagus. He was also partial to Périgord truffles and foie gras from Alsace. He loved lobster, fish and duck. In the late summer and fall, he enjoyed garlicky ceps. Though he wasn’t much of a wine connoisseur, he did like Loire wines and especially gave preference to a good Sancerre.

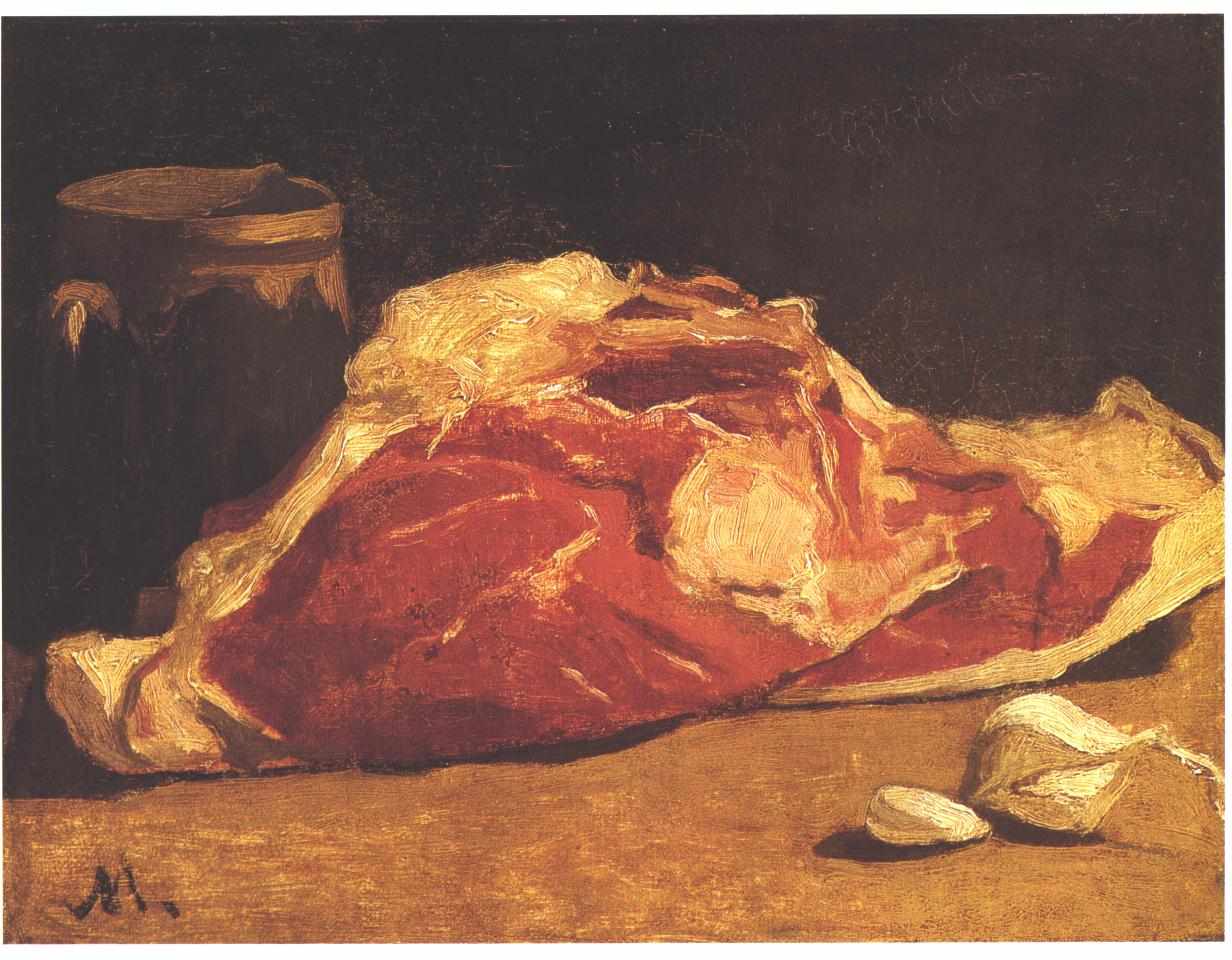

FOOD-RELATED PAINTINGS

One of Monet’s first food paintings was Still-Life: Quarter of Beef (c. 1864). In the sober, realist composition we see the food of the lower class French in the mid-19th century: a piece of beef, garlic for flavor and a ceramic mug, probably holding beer.

Still-Life: Quarter of Beef (c. 1864). Musée d’Orsay, Paris

By contrast, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1865-66), depicts an upper middle class feast of pâté en croûte, roast chicken, bread, fruit and wine. Under a softly dappled light, a fashionably dressed group has their food on fine china and uses crystal glasses for their wine. Though obviously an intimate setting, the painting is still inviting enough to almost prompt the viewer to take a seat and help themselves.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1866), Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow

The Luncheon (1868-69) captures a convivial, relaxed and carefree scene. His first wife, Camille is at the table with their young son. It is an autobiographical painting rendered at a time when the artist was able to adequately provide for his family after receiving payment from one of his patrons.

The Luncheon (1868-69), Städel Museum, Frankfurt

Some of Monet’s most delectable still-lifes were Still-Life with Melon (1872) and The Galettes (1882). In the first, we see sweet, ripe summer fruits, and in the second, two beautifully golden galettes waiting to be sampled with some cider (seen in the carafe).

Still-Life with Melon (1872), Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon

The Galettes (1882), private collection

COOKING WITH MONET

In the second part of this post, I will tell you about a cookbook that any Monet fan, history buff and lover of gorgeous French food will want to add to their collection. It is a book that will not only inspire you with some of the recipes that emerged from Monet’s kitchen, but also give you a look into the life of one of the greatest French painters. Monet died on December 5th 1926, but continues to delight the senses through his paintings and recipes.

Image shown at the top of this post: Portrait, 1899, Nadar